Art and trademark law

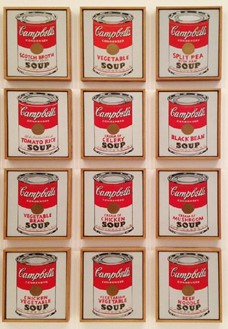

24 June 2021Andy Warhol created the world-famous artwork of a series of Campbell’s soup cans in 1962. Although this artwork was made without Campbell's permission, the manufacturer did not react negatively. In fact, Warhol was admired for his artwork and sent several cans of soup.

This is a positive example of using a brand in art. However, the reality is that such usage usually sparks debate. There is then a clash between the freedom of expression of the artist on the one hand and the trademark right of the trademark owner on the other. It is interesting to examine this field of friction, and consider both the possibility and desirability of allowing artistic freedom to prevail over trademark law. It is not entirely unimportant whether artists have a commercial objective in this regard.

Both the Trademark Directive and case law show that the right to freedom of expression, and thus artistic freedom, can be a valid reason for trademark infringement. Both commercial brand use and non-commercial brand use by third parties can, in principle, be protected on the basis of art. 10 ECHR of the European Convention on Human Rights. The Benelux Court of Justice has ruled that the degree of commercial character is important in the assessment.[1] The protection of commercial expressions is therefore lower than that of non-commercial expressions.

In trademark law, the issue of ‘parody’ deserves attention. A parody is an imitation by means of an adaptation of the original, resulting in a humorous, critical, ironic, or mocking effect. In this way, a sensitive subject can be broached. For this reason, parodies also fall within the scope of the right to freedom of expression and the right to artistic freedom. The purpose of the parody plays an important role in weighing usage rights. The distinction between a parody with an idealistic goal and a parody with a commercial goal is important for the degree of protection. An ideal parody uses a brand to make a statement.

An example of an ideal parody in trademark law is found in the judgment, the Dutch State v. Greenpeace, in which Greenpeace placed a banner on a government building. [1] The banner bore the brand 'THINK AHEAD', an information campaign by the Ministry of the Interior. Greenpeace placed this banner in the run-up to the parliamentary elections on November 22, 2006 to draw attention to the potential dangers of nuclear energy and to protest against it. In a purely commercial parody, on the other hand, a brand is only used to get more attention for the expression of the parodist. In this case there is no question of social interest playing a role, or of a critical message requiring expression.

The desirability of artistic freedom as a valid reason is apparent from various theories of justification. An important theory is that of the discursive democracy by Rosemary Coombe. This theory justifies the freedom to influence the meaning of brands. Society and consumers play a role in influencing the meanings of brands. A good example of this is the 'Barbie' brand. Mattel, an American toy manufacturer, has spent a long time building the image of the Barbie doll. Although the doll has become a popular toy, the 'Barbie' brand symbolizes dumb blonde. In addition to the theories of justification, case law also shows the desirability of artistic freedom as a valid reason for trademark infringement.

The desirability of artistic freedom as a valid reason is apparent from various theories of justification. An important theory is that of the discursive democracy by Rosemary Coombe. This theory justifies the freedom to influence the meaning of brands. Society and consumers play a role in influencing the meanings of brands. A good example of this is the 'Barbie' brand. Mattel, an American toy manufacturer, has spent a long time building the image of the Barbie doll. Although the doll has become a popular toy, the 'Barbie' brand symbolizes dumb blonde. In addition to the theories of justification, case law also shows the desirability of artistic freedom as a valid reason for trademark infringement.

Do you have any questions about this? Please feel free to contact us.

[1] Rb. Amsterdam 22 December 2006, ECLI:NL:RBAMS:2006:AZ5624, (State/Greenpeace).

[1] BenGH 14 October 2019, A 2018/1/08, (Moët Hennessy/Cedric. Art).